Row, row, row your boat gently up/down the stream???

Purpose: This blog post is created to help readers a) better understand electronic compass [smartphone or rangefinder] residual azimuth deviation errors b) quantify the errors, c) model the errors, d) compensate for [correct] the errors, and e) influence their app vendor to apply the correction method within the affected smartphone app. Basically, we need to know (accurately) whether to go up / down the stream (path) we are traveling on.

Background:

This post will present and compare field test results of the a) Vectronix PLRF25C (with compass) laser rangefinder, b) Sig Sauer 2400ABS (with compass) rangefinder, and c) iPhone/Theodolite compass app operated at the Birmingham, AL test site with a strong magnetic/electromagnetic field.

The Birmingham, AL test site is set in an urban environment with strong magnetic/electromagnetic influences including:

- An electric power distribution station for eight (8) townhomes

- At least eight operating heating/cooling (heat pump) units of 3 to 4 ton capacity – aligned North/South within 50 feet of the test site (East side)

- An active highway – aligned North/South within 150 feet of the test site (West side)

The data collection equipment and procedures used at the test site (Birmingham, AL) were identical to those used previously and reported in prior blog posts.

- The reference direction (True North) was established using sun position – a correct, defendable, and independent reference direction.

- True North (reference direction) was established based on the sun position relative to the test site’s geographic location on the date/time of each test.

- The Vectronix, Sig Sauer, and iPhone compasses were set to indicate azimuths relative to True North.

- The Vectronix, Sig Sauer, and iPhone compasses were all calibrated prior to the start of the data collection operations.

Recall: The residual compass deviation error persists throughout the entire 360 degree range of measurement.

Note: The Vectronix and Sig Sauer rangefinders are operated only in the vertical “Portrait” orientation – normal operation; while the iPhone/Theodolite compass app was operated only in the “Landscape” orientation – normal operation.

Observations, Conclusions, and Objective

Extensive research has led the author to assimilate the following observations and conclusions.

- Observation A: “Multi-sensor imaging systems using the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) and digital magnetic compass (DMC) for geo-referencing have an important role and wide application in long-range surveillance systems. To achieve the required system heading accuracy, the specific magnetic compass a) calibration and b) compensation procedures, which highly depend on the application conditions, should be applied. The DMC compensation technique suitable for the operation environment is described and different technical solutions are studied. The application of the swinging procedure was shown as a good solution for DMC compensation in a given application.” Reference: Digital Magnetic Compass Integration with Stationary, Land-Based Electro-Optical Multi-Sensor Surveillance System, by Branko Livada * , Saša Vuji´c, Dragan Radi´c, Tomislav Unkaševi´c and Zoran Banjac, Vlatacom Institute, Milutina Milankovi´ca 5, 11070 Belgrade, Serbia, Link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6806335/pdf/sensors-19-04331.pdf

- Conclusion A: In this present work, the author a) examines the accuracy of two reputable handheld laser rangefinders [with their digital magnetic compasses] and the smartphone (iPhone) app Theodolite and b) applies [after invoking the manufacturer’s own compass calibration procedure] the compensation algorithm/procedure [the compass swinging procedure] to correct for erroneous compass azimuth readings. The application of the compass swinging procedure is shown to be a good solution for residual (after calibration) azimuth deviation error compensation in a given application setting.

- Observation B: Basically, the handheld laser rangefinder industry provides two fundamentally different classes of products to two fundamentally different markets: a) consumer market and b) military market. Two common rangefinder components [used in both markets] are a) the ranging element itself and b) the electronic compass. For the military market, the ranging element must be able to range to far greater distances than needed for the consumer market – with a significantly (orders of magnitude) higher-price/distance-ranged capability than in the consumer market. For the military market, the compass (North-finding) capability must be more reliable and accurate (to a higher degree than is required by the consumer market) with a significantly higher-price being paid for the additional military capability requirements. However, for some applications areas, the consumer market approaches both the range and compass (azimuth finding) requirements of the military market.

- To be certain, both the consumer and military rangefinder markets run up against the same obstacle (flaw) in the compass (azimuth finding) capability – the variations (deviations) in the earth’s magnetic field strength and the azimuth errors those variations create.

- For the military market, the vendor solution is to add more expensive/more sophisticated electronic compass components and technology (e.g., solar compasses). For the consumer market, the vendors have not provided an adequate solution for the residual compass azimuth error – expensive consumer grade laser rangefinders (typically) just have cheap electronic compasses to keep the price down.

- Vendors of consumer grade rangefinders (with compass) infer that they don’t have to upgrade the compass component; because the market is not out there – not enough market volume. Potential users of compass-enabled laser rangefinders infer that they don’t use the consumer-grade technology anyway; because the compass capability (accuracy) is not sufficient to warrant its use with sophisticated applications – these users just hire a licensed land surveyor with their very expensive “Total Station” equipment, if these users make the effort at all. Thus the consumer market for capable (long range & compass accuracy) just does not exist – except for a few unique, custom, bulky applications. For those higher-value applications that do exist, the users frequently wind up paying military-grade (somewhat equivalent) prices. Which comes first, the chicken or the egg? Stated another way, “Which will come first, the higher-value volume rangefinder applications or the capable compass accuracy?”.

- Conclusion B: Since both the military and the consumer rangefinder markets can both use more accurate compass (azimuth) capability, the “common” compass accuracy issue should be solved first – that’s the weak link. The ranging capabilities seem to be aligned (already) within the two markets. Perhaps this practical method for compass error (deviation) compensation would be a welcome solution in both markets?

- Observation C: In many industries and in many higher-value application areas there is a need to document/map the 3D geodetic (geographic) location of some relevant remote object – object locations that cannot be “occupied”. Sometimes, the relevant object’s geodetic (or map) coordinates need to be obtained to the accuracy of a legal land survey. At other times, the accuracy of a legal land survey is entirely “overkill” in terms of time-to-get-it-done, money, and just plain usefulness (just-good-enough). It’s toward these “other times” that the contents of this work are directed.

- Conclusion C: The determined, effective user of map information should be able to acquire a well-equipped handheld laser rangefinder (Vectronix PLRF25C [military grade rangefinder], Sig Sauer KILO2400 [hunting/shooting consumer grade rangefinder] or a LaserTech TruPulse 360 [professional grade rangefinder]) and get their job done – with the necessary and sufficient compass azimuth accuracy.

- Observation D: Personal experience has shown that the electronic compasses integrated into commercial grade handheld laser rangefinders leave a lot to be desired in terms of their ability to provide an accurate azimuth reading. In fact, those most knowledgeable of the industry (the rangefinder vendors) actively discourage the use of commercial grade rangefinders to determine the “single shot” solution to the remote target localization problem because of the persistent lack of quality results from the electronic compass – the azimuth determination. Almost all of the laser rangefinder vendors a) prescribe the use of multiple “shots” of the laser rangefinders (from multiple known [surveyed] reference points) and b) employ [indirect] triangulation techniques to solve the remote target location problem – most often, using expensive third party GIS software and requiring expensive highly trained GIS “specialist” operators.

- Conclusion D: This author deplores the use of such inefficient (wasted motion/time/cost) techniques; and this author expects to provide the laser rangefinder operator (user) with a more accurate/more efficient (single shot) solution for determining the geographic location of remote targets – in the not too distant future.

- Observation E: Every user of handheld laser rangefinder equipment is aware of the old saying “You get what you pay for!” Every competent laser rangefinder user is aware of the “practical” level of accuracy needed to get his job done effectively and efficiently. The “just-good-enough” solution if often all that is needed to get-the-job-done right the first time.

- Conclusion E: With today’s laser rangefinder technology, there should be no logical reason to require only expensive military grade handheld laser rangefinders (costing tens of thousands of dollars and capable of providing military grade compass azimuth accuracy levels) to solve the remote target location problem in a manner satisfying the requirements of the “job at hand”. That should be the case whether the job involves a) locating personal photos, b) locating eagles’ nests, c) documenting archaeological sites, d) targeting game in a hunting situation, or e) locating remote facility positions on a construction site. Neither should the user be constrained to use unfamiliar map projection techniques and/or expensive third party GIS software (and operators) to get the job done. For the author, “Give me a rangefinder (with compass) and a smartphone mapping app that works; and I’ll get the job done in a reasonable time period and at a cost appropriate to the requirements of the job”.

Objectives: This work intends to present a straightforward, practical method for correcting (compensating) reasonably expected residual electronic compass deviation errors associated with the use of a variety (varied price points) of handheld laser rangefinders and smartphone compass apps. Also, this work intends to introduce disruptive technology into the laser rangefinder industry and into the smartphone compass app industry.

The author is fully aware that some users can accept a lower accuracy level provided “out-of-the-box” – as is; while other users are willing and able to perform a calibration/recalibration of the electronic compass when needed – even to the extent of “going the extra mile” and determining compass error compensation values. It all depends on the importance of compass azimuth accuracy to the job at hand.

- In general, accurate ship navigation over the open seas is more important (worth more in terms of cost and time required) than bird-watching; but that determination should be up to the individual performing the task at hand.

- However, the “calibration/recalibration” process for the rangefinder (electronic compass) instrument must be simple enough to implement while not adding excessive additional cost to the process.

- Likewise, any azimuth error compensation method must be simple enough to implement while not adding excessive additional cost to the overall process of getting better accuracy out of the electronic compass.

- Again: “To achieve the required system heading accuracy, the specific magnetic compass a) calibration and b) compensation procedures, which highly depend on the application conditions, should be applied.“

Note: The author is fully aware that compass tilt is a big contributor to compass azimuth error. However, there are several consumer grade electronic compasses (available, reasonably priced, and integrated with tilt compensation hardware/techniques) that correct for compass tilt. The compass user should be aware that he/she should a) attempt to avoid compass tilt or b) use a compass capable of compensating for compass tilt. The methods presented in this work are not intended to deal with (solve) the compass tilt issue.

It is easy to understand that quality compass azimuth results are of paramount importance to the solution of the remote target location problem.

For the Reader’s Benefit: The author has been thorough in this work solely for the purpose of presenting a volume of facts and examples that are true to the accomplishment of the objectives stated above. The remainder of this text will prove (completely) the following points.

- For the electronic compass (and magnetic compasses), residual azimuth deviation errors can be corrected using the deviation curve (compensation) approach.

- The use of the deviation curve compensation approach cannot correct faulty operator errors.

- Once prepared, the deviation curve(s) for a given electronic compass can be used over a long period of time – provided areas of magnetic/electromagnetic influence are not encountered on a regular basis.

- The compass deviation curve(s) can be effectively used beyond 600 miles of the North/South poles; and that covers a lot of territory.

- Relocation to a new project area (also free of local zones of magnetic/electromagnetic interference) does not require reconstruction of the deviation curve(s).

- It is a good idea to configure the operator and/or the operator’s equipment package (as he/she would be operating in-the-field) before attempting to prepare compass deviation curve(s). In other words, account for local magnetic interferences (experienced while the measurements are being taken) before preparing compass deviation curve(s).

- With regard to the use of an electronic/magnetic compass, it is important that the user/operator be aware of the operating environment and the sources of electromagnetic/magnetic disturbing influences within relatively close proximity to the compass instrument. The author acknowledges that, to some extent, local environmental disturbing influences may be accounted for by recalibration of the compass instrument. However, in most cases, recalibration of the compass is not sufficient enough to be meaningful with regard to residual azimuth deviation errors.

The Work

The work presented here deals with the determination of and compensation for electronic compass residual (after calibration) azimuth deviation errors of the Vectronix PLRF25C (military grade) laser rangefinder, the Sig Sauer 2400ABS (consumer grade) laser rangefinder, and the iPhone/Theodolite compass app. In prior posts, the Vectronix rangefinder and the iPhone/Theodolite compass app have been dealt with extensively.

Specifically, the Sig Sauer 2400ABS laser rangefinder (manufactured for long-range shooting) is the focus of this study; because it provides a) high quality optics, b) high quality laser range finding capability, and yet c) very weak compass azimuth determination capability. Observation: The Sig Sauer 2400ABS laser rangefinder is a $1500 quality rangefinder with a “$2” electronic compass! Assertion: Long-range shooting (as an application) does not require quality azimuth determination – apparently. This observation/assertion confirms “Observation D” stated above.

This application (case study) of the azimuth error compensation method (represented in this post) proves that even inadequate (erroneous) electronic compass results can be corrected significantly. Both the Vectronix rangefinder and the iPhone/Theodolite compass app have been tested and demonstrated to exhibit “significant” residual azimuth deviation errors in prior posts. Yet the compensation of such azimuth errors (from both devices) has been demonstrated as being highly effective in significantly reducing that error.

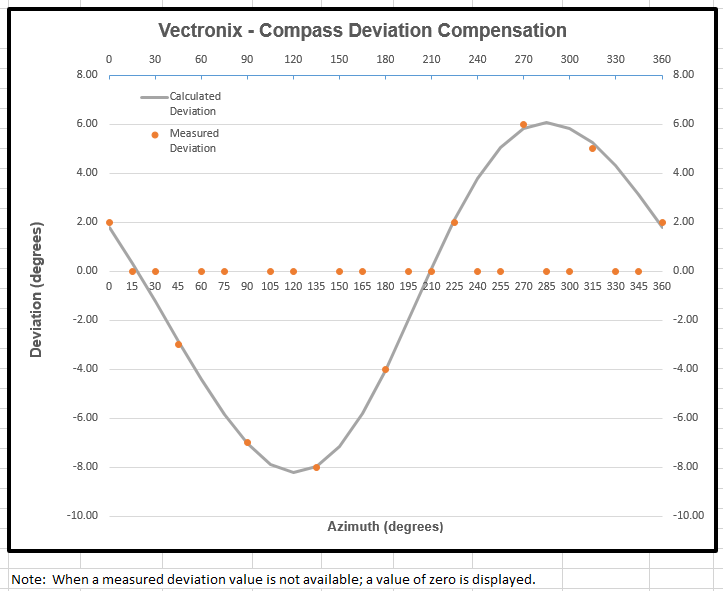

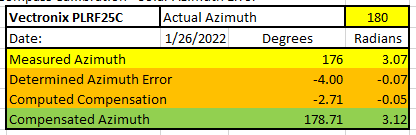

Vectronix PLRF25C Handheld Laser Rangefinder (military grade)

The following table depicts a compensation of the measured Vectronix azimuth deviation error to leave a remaining azimuth error of only -1.29 degrees.

Takeaways from the two previous charts:

- Vectronix Error Range: -8.2 < Deviation Error < +6 degrees

- Vectronix Measured (test) Azimuth Deviation Error = -4 degrees

- Compensated (remaining) Azimuth Error = -1.29 degrees

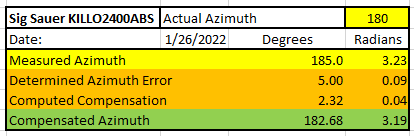

Sig Sauer KILO2400ABS Laser Rangefinder (consumer grade)

The following table depicts a compensation of the measured Sig Sauer KILO2400ABS azimuth error to leave a remaining azimuth error of only +2.68 degrees.

Takeaways from the two previous charts:

- Sig Sauer Error Range: -18 < Deviation Error < +28 degrees

- Sig Sauer Measured (test) Azimuth Deviation Error = +5 degrees

- Compensated (remaining) Azimuth Error = +2.68 degrees

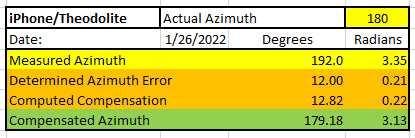

iPhone/Theodolite compass app (iPhone 12 MAX)

The following table depicts a compensation of the iPhone/Theodolite azimuth error to leave a remaining azimuth error of only -0.82 degrees.

Takeaways from the two previous charts:

- iPhone/Theodolite Error Range: +0.8 < Deviation Error < +18 degrees

- iPhone/Theodolite Measured (test) Azimuth Deviation Error = +12 degrees

- Compensated (remaining) Azimuth Error = -0.82 degrees

Thus, considering prior posts and the data presented in this case study, it has been substantiated that the compensation method used here corrects residual compass azimuth deviation errors significantly for electronic compasses used in laser rangefinders (whether military or commercial grade) as well as in smartphones such as the iPhone.

Recall that the methods presented in prior posts and in this post can be effectively used to assess and compensate the residual compass azimuth deviation errors for a) any electronic compass, b) any laser rangefinder [with compass], and c) any smartphone compass app. Also, this compensation method can be readily adapted by vendors of laser rangefinders and/or smartphone compass apps.

In future posts, the author plans to evaluate additional commercial grade laser rangefinders (with compass). There’s more to come!

3 responses to “Fixing Rangefinder & Smartphone Residual Compass (azimuth) Deviation Errors – Vectronix PLRF25C vs Sig Sauer 2400ABS Rangefinder”

-

I couldn’t agree more

Great post! I found the comparison of field test results of different handheld laser rangefinders and smartphone compass apps to be very informative. My question is, have you found any compass accuracy issues with other brands of laser rangefinders or smartphone compass apps?

Jon

http://www.airiches.online/LikeLike

-

Jon: Please take a look at the prior post where I cover Compass 55, Compass Deluxe, SpyGlass, and Theodolite compass ApS in detail.

I plan to assess LTI TruPulse and Haglof rangefinder’s.

JimLikeLike

-

John: Yes!

Sig Sauer rangefinders have very poor electronic compasses – as most others do.

I have found that all smartphone compass apps fail the accuracy test.

JimLikeLike

-

Leave a comment